Clay illustration by Lily Offit; Photographed by Ben Denzer

Cynthia Y Tang, BS [1]*, Lauren E. Flowers, BS [1]*, Emra Bosnjak, BS [1] , Tricia Haynes, MS [1] , Jamie B. Smith, MA [2] , Laura E. Morris, MD, MSPH [2]

[1] School of Medicine, University of Missouri

[2] Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri

*These authors contributed equally to this study

Correspondence should be addressed to Laura E. Morris, MD, MSPH at morrislau@health.missouri.edu

ABSTRACT

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable deaths and diseases in the United States. Student-run clinics play an invaluable role in connecting underserved patients with preventative care. To reduce smoking in uninsured communities, the University of Missouri student-run free MedZou Community Health Clinic developed a Smoking Cessation initiative as part of a preventative health service in 2013. Patients utilizing the smoking cessation services receive a combination of motivational interviewing, patient education, and pharmacotherapy. There is currently limited literature on the structure and implementation of student-run preventative health clinics. The smoking cessation initiative described here can provide an example for other student-run clinics to successfully implement similar programs.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States, accounting for 20% of all deaths [1, 2]. Tobacco use is a risk factor for pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases and has been linked to diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and various cancers including lung, liver, colorectal, prostate, and breast cancer [3-5]. Additionally, secondhand smoke exposure is associated with pediatric respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and cancers [3-5].

In the United States, the percentage of adults who use tobacco products has increased from 19.3% to 20.8% between 2017 and 2019 [2,6]. Adults living in the Midwest have the highest regional prevalence of tobacco use (23.5%), and Missouri has the tenth highest smoking rate amongst all states nationwide [2,7]. Additionally, prevalence is higher among those who have an annual income of less than $35,000 (26.0%) and those who are uninsured (31.0%) compared to those in higher income categories and those with health insurance [2].

Preventative services, including routine screening and monitoring, can reduce mortality and morbidity in at-risk populations [8]. However, uninsured populations are less likely to prioritize and regularly see primary care providers for preventative services, putting them at higher risk of adverse health outcomes [9]. Many uninsured patients are cared for in free or reduced cost clinics, and thus, improving prevention measures in a free clinic could significantly impact patient outcomes.8 Therefore, implementation of comprehensive and evidence-based interventions in combination with barrier-free cessation coverage can reduce tobacco-related disease [6].

The MedZou Clinic

The University of Missouri School of Medicine student-run free MedZou Community Health Clinic is an interdisciplinary, faculty-sponsored, weekly medical clinic for uninsured persons that is managed entirely by the University of Missouri’s medical student volunteers. MedZou opened in 2008 as an initial response to a 2005 decrease in Missouri Medicaid funding, which resulted in an increase of 103,500 newly uninsured individuals across the state between 2004 and 2006.10 As of 2019, 877,591 adults (between ages 18 and 64) lack health insurance in Missouri, and the uninsured rate (14.3%) is higher than national average (12.9%) [11]. In the MedZou clinic location of Boone County, 12% of adults (approximately 21,000 adults) are uninsured [12]. To address this rise in the uninsured and underinsured populations, MedZou offers free primary healthcare and preventative services to uninsured residents of Central Missouri, including some medications, diagnostic testing and routine bloodwork. From its inception, over 800 medical students have volunteered at MedZou to serve a total of 1,902 unique patients. In 2013, MedZou expanded to include a Preventative Health Clinic described here, involving over 180 medical student volunteers, which provides uninsured and underinsured populations with access to smoking cessation tools.

METHODS

Preventative Health Clinic

The Preventative Health Clinic at MedZou was created in 2013 to decrease the risk of adverse health events for the MedZou patient population. More than 180 medical students have since been trained to volunteer weekly as part of the physician-supervised Preventative Health Team (PHT) to provide community resources, substance counseling, diet and exercise counseling, HIV testing, influenza vaccination, vision care, safe sex education, and smoking cessation counseling. In Boone County, Missouri, 18% of adults smoke [13], and one of the most widely used preventative services offered at the MedZou clinic is the Smoking Cessation Program. The free weekly Smoking Cessation Program at MedZou clinic integrates patient education and motivational interviewing with pharmacotherapy to decrease the prevalence of smoking in the uninsured and underinsured populations. Preventative health initiatives at the MedZou Community Health Clinic bring smoking cessation services directly to a population with difficulty accessing traditional healthcare.

Prevention, Intake, and Trauma Team Transition

Prior to 2019, nursing students completed the intake process and initial patient vitals. Afterwards, PHT students would perform preventative health questionnaires intake questions. However, PHT students responded only to those patients who indicated interest in tobacco cessation services on the routine intake questionnaire. Students recognized that this approach required patients to actively self-report a desire to quit smoking to engage with the preventative services of PHT, potentially resulting in underutilization of smoking cessation resources. In 2019, the role of the PHT expanded to include intake vitals and trauma screening, and was renamed the Prevention, Intake, and Trauma Team (PiT). PiT medical students now approach every MedZou patient to obtain vital signs, screen for mental health disorders and interpersonal trauma, evaluate needs for social work or dietetics assistance, and assess interest in preventative care, including smoking cessation. The transition from PHT to PiT has streamlined the intake process for MedZou patients, shortened the duration of their visit, and allowed preventative health screening for every MedZou patient.

Volunteer Training

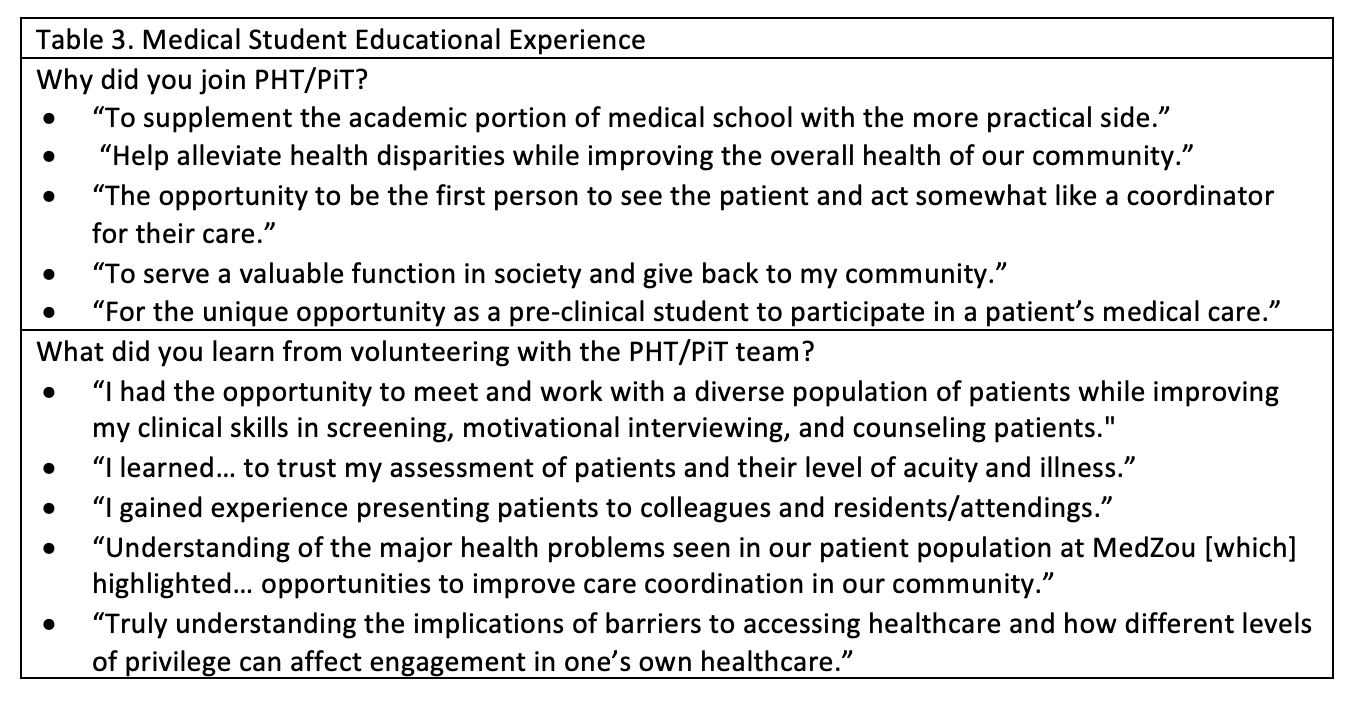

MedZou leadership positions, including the PiT volunteer team, are passed from second-year medical students to first-year students through an application and interview process. Each student with a leadership position is required to complete a minimum of five volunteer shifts at the MedZou clinic prior to completion of medical school. Thus, students return to volunteer at MedZou clinic multiple times during their third and fourth years. To prepare for patient interactions, motivational interviewing is integrated into the pre-clerkship medical curriculum at the University of Missouri School of Medicine [14-18]. PiT volunteers are additionally trained to provide counseling for smoking cessation by Certified Tobacco Treatment Specialists from the Columbia/Boone County Public Health and Human Services Department and the Columbia Health and Wellness Resource Center. Drawing upon this training, students follow a general “5 A’s” outline for smoking intervention (Table 1). Students further develop cessation plans under physician supervision based on several questions (Table 2) asked during the visit. Smoking cessation conversations are inclusive of any tobacco or nicotine product, including electronic cigarettes, and offers patients pharmacotherapy, community resources, and brief counseling. Students are trained to understand the stages of behavioral change and can appropriately manage a patient’s resistance or ambivalence to change. The knowledge acquired through PiT trainings empowers medical students to establish a partnership with MedZou patients and become an active role in their health care journey. Table 3 highlights testimonies from five previous PiT volunteers to assess the value of the PiT volunteer experience on the student’s medical education. Students perceived their experiences to supplement early medical school training and support their knowledge of healthcare disparities in the MedZou community.

Clinic Flow

After patients are escorted into a clinic room, PiT volunteers take vital signs, identify any food and housing security needs, screen for mental health disorders and interpersonal trauma, and assess interest in preventative services. Students screen every patient for tobacco use and follow motivational interviewing techniques if a patient screens positive. Students then present this information to the attending physicians and develop a plan for patient care. After the PiT students provide smoking cessation education, patients may choose to use a pharmacologic smoking cessation agent with the approval from the attending physician. Smoking cessation pharmacotherapy includes nicotine patches and nicotine gum as well as physician-generated prescriptions for bupropion and varenicline. Following this initial visit, patients are encouraged to schedule a standalone 2-week follow-up visit with the PiT student volunteers for further counseling or behavioral changes toward smoking cessation. Subsequently, each patient is scheduled for routine follow-up visits with physicians at MedZou clinic. These standalone PiT visits in combination with followup clinic visits allow PiT to improve longitudinal care and continually assess smoking cessation progress.

Telehealth

In 2020, MedZou temporarily transitioned to only telehealth appointments due to social distancing restrictions related to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The PiT volunteers continued to screen all patients for tobacco and nicotine habits, and student training protocols remained the same. Due to time constraints of telehealth visits, personalized counseling with motivational interviewing techniques was limited. Patients interested in smoking cessation scheduled pick up of cessation supplies at the MedZou clinic, which included nicotine replacement therapy (patches or gum), information for community cessation resources, and a personalized cessation plan. The cessation plan provided patients with a tangible outline of personalized motivations, possible triggers, and coping mechanisms for managing these behavioral changes. Patients also scheduled a two-week telehealth follow-up appointment to evaluate behavioral change progression. Although this temporary transition was not ideal, patients were still able to receive the benefits of PiT smoking cessation initiatives.

The Preventative Health Clinic at MedZou provided smoking cessation consults and treatment for 110 adult patients from 2016-2019, 40 of whom returned for the recommended two-week follow-up. Patient demographics, number of years smoking, and smoking classification of those patients are shown in Table 4. Our smoking cessation program patient population was comprised of 61% females, 39% males, 71.4% White, 25.3% Black, and 3.3% Other, and 68.8% Non-Hispanic. The average age at first visit for our study population was 41.4 years. In comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the demographics of smoking adults are highest among males, between ages 25-44 and 45-64, and non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives and people of non-Hispanic Other races [1].

Of the 57% of patients who chose to pursue pharmacotherapy during their first visit, Nicotine Patch (22%) or Nicotine Gum (14%) were the most chosen pharmacological agents to aid smoking cessation. The smoking cessation agents chosen by the patients are noted in Figure 1. Nicotine patches and nicotine gum are supplied to MedZou by the Columbia-Boone County Health Department, bupropion is supplied by the University of Missouri Pharmacy, and varenicline is supplied by Pfizer Inc.

Figure 1. Smoking Cessation Agents. Pharmaceutical agents chosen and provided to patients at the conclusion of the first clinical visit to the Preventative Health Clinic.

CHALLENGES

Because MedZou serves the uninsured, underinsured, and often homeless populations, our patients are frequently lost to follow-up. Contacting patients outside of the clinic proved to be especially difficult, as many patients do not have a consistent address or access to a phone or computer. This poses a challenge to continuation of care as well as a limitation to our ability to assess the success of the smoking cessation program. This challenge was especially heightened during the COVID-19 global pandemic, which forced the MedZou clinic to temporarily operate on a solely telehealth basis. To facilitate communication with patients who would otherwise be lost to follow-up, MedZou clinic volunteers and members of the PiT team continuously work with the MedZou Outreach Team to hold outreach events around the community. This has allowed clinic volunteers to continue reaching out to patients who might not be able to regularly attend clinic. We recommend further investigations to evaluate additional solutions to mitigate these challenges.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this project was three-fold: to assess the utilization of the Smoking Cessation initiative at MedZou, to provide a framework for other student-run clinics to implement a similar program, and to expand awareness of the services that MedZou offers. Smoking has diverse health implications that can be prevented through smoking cessation services provided directly to at-risk patients. Preventative health initiatives at the MedZou Community Health Clinic bring smoking cessation services directly to a population with difficulty accessing traditional healthcare. While other student-run clinics have implemented similar preventative health programs with varying success, there is limited literature on the structure and implementation of these clinics [19-22]. Another student-run clinic in Phoenix, Arizona, found that in the homeless population, smoking cessation education and motivational interviewing techniques combined with pharmacotherapy slightly increased the patient’s confidence and willingness to quit [19]. The researchers in this study also struggled maintaining follow-up appointments with a similar patient population and specific motivational interviewing techniques were not described.

Finally, MedZou provides medical students at the University of Missouri an early and immersive experience in the clinic setting prior to clerkship rotations. The MedZou clinic experience imparts a non-judgmental environment for students to develop patient interaction and oral case presentation skills. Additionally, participation in the PiT team provides a unique opportunity for medical students to practice and advance motivational interviewing skills throughout their entire medical school training while serving the community. Students directly invest in and improve the health of a marginalized patient population within their own community through provision of preventative health services and the Smoking Cessation Initiative.

CONCLUSION

This study provided insight into training protocols and specific motivational interviewing techniques used by medical students at the MedZou Community Health Clinic. The Smoking Cessation initiative allows students to bring preventative health services directly to patients with limited access to traditional healthcare and help alleviate the diverse negative health implications associated with tobacco use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the PHT for their dedication and commitment to the Smoking Cessation Initiative, Samantha Unangst (Quality Improvement Chair), and Dr. Joseph Burclaff for his critical input.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interest to declare. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/ index.htm. Accessed January 22, 2022.

Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225-1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2.

Bartal M. Health effects of tobacco use and exposure. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2001;56(6):545-54. PMID: 11980288.

Mackenbach JP, Damhuis RA, Been JV. De gezondheidseffecten van roken [The effects of smoking on health: growth of knowledge reveals even grimmer picture]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2017;160:D869. PMID: 28098043.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. PMID: 24455788.

Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736-1742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4.

Tobacco Use Prevention and Control. Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. https://health.mo.gov/living/wellness/tobacco/smokingandtobacco/tobaccocontrol.php. Accessed May 17, 2021.

Burger M, Taddeo MS, Hushla D, Pasarica M. Interventions for Increasing the Quality of Preventive Care at a Free Clinic. Cureus. 2020;12(1):e6562. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6562.

Holden CD, Chen J, Dagher RK. Preventive care utilization among the uninsured by race/ethnicity and income. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.029.

Zuckerman S, Miller DM, Pape ES. Missouri's 2005 Medicaid cuts: how did they affect enrollees and providers?. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):w335-w345. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w335.

Health Insurance Coverage of Adults 19-64. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-19-64/. Accessed January 3, 2022.

Boone County, Missouri. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/missouri/2019/rankings/boone/county/outcomes/. Accessed March 19, 2021.

Health Factors: Adult smoking, Missouri 2019. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/missouri/2019/measure/factors/9/map. Accessed October 14, 2019.

Le Houezec J, Säwe U. Réduction de consommation tabagique et abstinence temporaire: de nouvelles approches pour l'arrêt du tabac [Smoking reduction and temporary abstinence: new approaches for smoking cessation]. J Mal Vasc. 2003;28(5):293-300. PMID: 14978435.

Lee EJ. The Effect of Positive Group Psychotherapy and Motivational Interviewing on Smoking Cessation: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J Addict Nurs. 2017;28(2):88-95. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000169.

Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD006936. Published 2015 Mar 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub3.

Pócs D, Hamvai C, Kelemen O. Magatartás-változtatás az egészségügyben: a motivációs interjú [Health behavior change: motivational interviewing]. Orv Hetil. 2017;158(34):1331-1337. doi:10.1556/650.2017.30825.

Tuccero D, Railey K, Briggs M, Hull SK. Behavioral Health in Prevention and Chronic Illness Management: Motivational Interviewing. Prim Care. 2016;43(2):191-202. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2016.01.006.

Buckley K, Tsu L, Hormann S, et al. A health sciences student-run smoking cessation clinic experience within a homeless population. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(1):109-115.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.09.008.

Zucker J, Lee J, Khokhar M, Schroeder R, Keller S. Measuring and assessing preventive medicine services in a student-run free clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):344-358. doi:10.1353/hpu.2013.0009.

Lough LE, Ebbert JO, McLeod TG. Evaluation of a student-run smoking cessation clinic for a medically underserved population. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:55. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-55.

Der DE, You YQ, Wolter TD, Bowen DA, Dale LC. A free smoking intervention clinic initiated by medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):144-151. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63120-0.