Scout M. Treadwell [1], Maxwell R. Green [1], Sowmya Ravi [1]

Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana, 70112

Correspondence: STreadwell@tulane.edu

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed medical education for both preclinical and clinical students. Virtual learning, shortened rotation schedules, cancelled away rotations, decreased interactions with faculty and mentors, and other curriculum adaptions have had a profound effect on the learning opportunities students receive during their medical training. Research studies surveying US medical schools show students interested in dermatology have limited exposure to this specialty in the medical school curriculum, and the COVID pandemic has exacerbated this lack of clinical experience. This article serves as a review of proposed improvements and current adjustments that have been implemented amid the COVID-19 pandemic in medical schools across the country to address the unforeseen changes in dermatology medical education. General changes have included virtual dermatology electives, student involvement in teledermatology, and online mentorship programs.

INTRODUCTION

Beginning in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to extraordinary disruptions in medical education across the United States. To maintain CDC guidelines and prevent the spread of infection and decrease mortality rates, classes were moved online, instructors were delivering lectures virtually to maintain the integrity of medical student education, and students were deemed nonessential in the hospital on clinical rotations. Shadowing opportunities and clinical rotations for students were limited as minimum room occupancy guidelines were implemented and students were isolated from their peers, faculty, and advisors. In response to this shift of learning, innovative methods to continue to provide patient care and train medical students have been established.

Dermatological assessment is a vital diagnostic skill in clinical practice. Understanding skin pathologies is significant for all physicians; however, many medical graduates feel they were not adequately exposed to dermatology. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this lack of experience. Patients often present to non-dermatologists who may not know how to diagnose and treat dermatologic conditions. Research has shown that dermatologic diagnoses made by the primary care physician were concordant with that made by the dermatologists only 57% of the time (1). Thus, incorporating strategies to improve clinical education for all future physicians in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic conditions is imperative. Pre-pandemic, dermatology education was limited in the medical school curriculum (2). Research has shown that although dermatologic conditions have a high disease of burden, dermatology is not widely included in medical school curricula (3). Specifically, a study surveying 137 Allopathic US medical schools showed that only sixteen of the 137 schools had a course dedicated to dermatology in the first two preclinical learning years (3). Furthermore, only two of the surveyed schools required a third-year dermatology clinical rotation (3). While most medical schools incorporate dermatology lectures throughout broader educational systemic blocks, students must take the initiative to reach out to mentors in the field, set up shadowing opportunities, and plan for away rotations to establish a relationship with residency programs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these opportunities have been increasingly limited, and restrictions have made it difficult to learn from experts in this field (4). Without exposure to the field of dermatology throughout the entirety of the one’s medical school education, it may present as challenge for students matching into this field. This review serves a summary of the literature on how the COVID-19 pandemic has led to new innovative teaching methods in a virtual learning environment as well as suggestions on ways to improve student exposure to the field of dermatology.

METHODS

Two of us (S.M.T. and M.R.G.) independently identified studies published in February of 2020 to current date to account for the current pandemic that reported impact of COVID-19 on curriculum and learning changes in United States medical students’ preclinical and clinical dermatology education. We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were searched in December of 2021 using the terms ("Dermatology education" or "dermatology curriculum" or "dermatology knowledge") and ("medical school" or "medical student"). A total of 892 results were returned from this search. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA), we exported our search results into Covidence for systematic review management (5). After removal of duplicates, full-text articles were obtained if their abstracts were considered eligible by at least 1 of us. Each full-text article was assessed independently for final inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. Studies were included if they met all criteria below.

Inclusion Criteria

1. COVID-19 on curriculum and learning changes in United States medical students’ preclinical and clinical dermatology education.

2. Teledermatology in medical education.

3. Virtual mentoring opportunities for students interested in dermatology.

Results were limited to those published in 2020 to account for published articles on the current pandemic.

Exclusion Criteria

1. Dermatology residency training during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Dermatological manifestations of COVID-19 infection.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the literature search using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Adapted from http://prisma-statement.org.

RESULTS

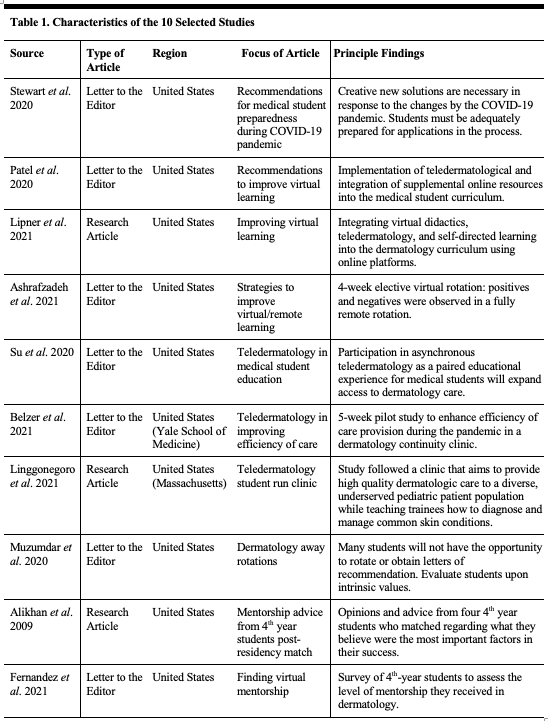

A total of 10 articles were included in this review, see Figure 1. A discussion of the role of the COVID-19 pandemic or its resulting effects on medical student dermatology curriculum and learning is summarized. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of the 10 included studies.

Virtual/Remote Learning

The traditional hands-on clerkship learning environment has been deconstructed due to the virtual changes the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed. To combat these alterations in learning, Patel et al. suggest the addition of a dermatology elective in the medical student curriculum to ensure students are comfortable and competent in the art of history taking, physical examination, documenting, and therapeutic management of common dermatological conditions (4). This proposed elective includes lessons on describing dermatology morphology and understanding the underlying pathophysiology causing the most common dermatology diagnoses. Virtual and online lectures can achieve this mission. Patel et al. also propose a flipped classroom approach that includes video learning so students can learn dermatologic procedures (4). Virtual platforms have been essential in continuing medical student dermatology education during the pandemic. The implementation of prerecorded dermatology lectures into medical student curriculum, proposed by Lipner et al., allows for students to learn at their own pace without the constraints of a socially distanced and limited occupancy classroom (6). Increasing access to virtual dermatology learning models for medical students may improve dermatology education and exposure.

A piloted virtual 4-week dermatology elective provided students the unique opportunity to participate in virtual patient care was well as learn from faculty. Students were able to collect a history via phone call conversations with patients. Students were also able to describe dermatology morphologies based on the photographs patients submitted. This allowed students to formulate a differential diagnosis and recommend further diagnostic screening tests to their assigned faculty mentor. Students wrote clinical notes on the patients they evaluated as well as gave oral pretentions of the patients they spoke with. Students consulted approximately 100 patients and were exposed to a variety of dermatology conditions including rashes, sarcoidosis or immunotherapy induce skin toxicities (7). Individuals involved in this pilot program received valuable feedback from their faculty mentor on their oral presentation and clinical consulting skills. All students reported a substantial increase in their prior dermatology knowledge and confidence (7). Because COVID-19 limits student presence in dermatology clinics, teledermatology serves a critical role in medical student education. This pilot virtual dermatology elective created by Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Dermatology serves as a positive model for other medical schools interesting in increasing student exposure to the field of dermatology amid the international pandemic (7).

Teledermatology

The role of telehealth visits has become increasingly important amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, many dermatology practices have relied on telemedicine to virtually assess and treat patients. Su et al. states that this shift in care provides a unique opportunity to educate budding dermatologists. They encourage student involvement in teledermatology appointments as this aspect of dermatology will remain an important component of future patient care (8). A teledermatology rotation can provide participating medical students the opportunity to eConsult cases in a self-directed manner which allows for an individual formulation of a differential diagnoses. Medical students are also expected to learn the importance of longitudinally monitoring patients with chronic dermatologic conditions during a global pandemic. The implementation of teledermatology visits expands access to dermatologic care and is complementary to traditional trainee education (8).

The burden of managing both virtual and in-person patients presents a challenge to dermatology practices. Nine Yale School of Medicine students created the Teledermatology Student Task Force aiming to enhance the efficacy of care provided during the pandemic in a dermatology continuity clinic (9). Volunteers of this task force were able to help schedule patient video appointments and upload any clinically important images to patient charts. Students were able to assist in patient education ensuring patients were familiar with operating a smartphone or tablet for the telemedicine visit as well as how to access and open their own patient chart during the appointment. This pilot program was able to contact 104 patients (9). Of the 104, 87 patients were successfully reached by phone by the student task force volunteers and 93% reported that the outreach was helpful (9). 78% of these patients were able to successfully complete a video visit with their dermatologist (9). This study shows the potential for medical students to learn from telemedicine visits as well as the student opportunity to support both physicians and patients leading to optimal utilization of teledermatology.

In 2020, a pediatric dermatology student-run clinic was established to provide dermatologic care to an underserved population whose health care disparities and inequities were widened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to pandemic restrictions, care was delivered virtually. Patients were able to submit photographs of their dermatology complaints and three pre-clinical students were able to learn from dermatology resident’s teaching sessions on the specific presentations (10). Students were also able to virtually take patient history under the supervision of the dermatology resident or attending. These interactions increased students’ skills in history taking and improved their basic dermatology knowledge (10). Creating more teledermatology student run clinics can provide students interested in dermatology pre-clinical mentors as well as increasing exposure to the field of dermatology while still delivering care to underserved patients amid a global pandemic.

Away Rotations

Due to program restrictions, away rotations have been limited for visiting medical students. Traditionally, away rotations were critical for developing connections with faculty and obtaining letters of recommendation (2). With these clinical experiences delayed or cancelled, many students are concerned that they will be at a disadvantage for matching into a residency program. Stewart et. al proposes recommendations ensuring the application process is equitable and fair for medical students applying into dermatology. Measures such as virtual didactics and grand rounds may allow student to interact with dermatology faculty (2). Muzumdar et al. also outlines the challenge away rotations in midst of a pandemic presents. They too note that limiting student rotations negatively affects students interested in applying to the highly competitive field of dermatology, specifically those with no home dermatology departments or limited experience in the field. Creative options for students limited to virtual away rotations include virtual lectures and grand rounds sessions, student participation in teledermatology care, and virtually engaging in case-based learnings sessions (11). This provides an opportunity for students to ask questions to current residents and faculty and have experience with a program they may have not had otherwise due to COVID restrictions.

Mentorship

Mentorship is a critical aspect of a successful medical career. Advice from a supportive mentor can change the trajectory for medical students. According to a study completed by Alikhan et al., 4 students who matched in Dermatology noted that having an encouraging mentor that provided invaluable advice was crucial in a successful match (12). Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, students are in an unprecedented position in which their access to mentorship is limited. Therefore, it is imperative to improve methods promoting more access to mentorship in dermatology. Minority students have reported that lack of a supportive mentor is an obstacle in applying to a dermatology residency program. In 2018, only 6% of dermatology faculty at medical schools across the United States identified as Black or Latino (13). Creating virtual dermatology mentorship programs can diversify student’s access to mentors. These programs can include alumni directories of clinicians in specific specialties as a resource for students. Web-based open houses hosted by program directors may also provide opportunities for students to establish connections with mentors, especially for students with no home institution (13). While forming a relationship with a mentor in a virtual setting may not develop as organically as an in-person interaction, the goal of a virtual mentoring program can increase access for students to find support within the field of dermatology.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review of alterations to dermatology teachings in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we found suggestions that have been implemented to improve curriculum in areas of virtual and remote learning, teledermatology, away rotations, and mentorship. These proposals can continue to be implemented to further improve medical school dermatology curriculum.

As with many other medical specialties, the field of dermatology has had to adjust to COVID-19 by improving virtual teaching options for students and expanding teledermatology care and education. In addition, the pandemic has limited student access to both away-rotations and mentorship opportunities, both vital components to the traditional undergraduate dermatology education for those interested in the field.

Although many adjustments were made to create virtual medical school curricula, students overall see a benefit in virtual learning for its increased flexibility with their study schedule (14). Additionally, no differences in the effectiveness of online versus offline medical education have been shown (15). These results argue in favor for the benefits of widespread online medical education that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, increased stress and burnout have also been associated with online learning platforms, suggesting that hybrid curricula with both on and offline components may be the most effective for medical students (16). A hybrid plan could include virtual lectures with in-person case-based team learning sessions.

The reduced access to both mentorship and away rotations is more challenging to tackle, but the creation of virtual away rotations may be an effective solution to both these issues. Virtual opportunities in the field of radiology increased student access to both rotation experience and mentorship while lowering the costs associated with traditional away experiences; the largest reported drawbacks were delays for students and technical difficulties (17). Increased access to rotations was also observed with virtual plastic surgery rotations, but students felt that it was difficult to connect and stand out through a virtual platform (18). Although these same challenges faced by other medical specialties with virtual rotations would likely be experienced in dermatology, the benefits of creating more virtual programs to improve access may be worthwhile. Traditional away rotations add an extra cost for medical students and the cost associated may disadvantage students from completing rotations and establishing relationships with non-home programs. Establishing more virtual away rotations will decrease financial burden and may increase opportunities and equity for all students interested in going into dermatology.

CONCLUSIONS

The effects of COVID-19 on undergraduate dermatology education will likely outlast the pandemic itself, so using the lessons learned over the past two years is essential for continuing to strengthen the field of dermatology. The current literature demonstrates improvements and suggestions that have been implemented to account for the rapid classroom changes imposed by the ongoing pandemic. These recommendations have taken into account the importance of continuity in medical student education and have increased exposure for students virtually in a time defined by isolation. Furthermore, as the pandemic continues to evolve, it is crucial to continue to adapt current models to ensure students interested in dermatology have access to knowledge, mentorship, and feel confident applying for a residency position in this field.

DISCLOSURES

Funding: Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Consent to participate: Not applicable.

REFERENCES

1. Lowell, B. A., Froelich, C. W., Federman, D. G., & Kirsner, R. S. (2001). Dermatology in primary care: Prevalence and patient disposition. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 45(2), 250–255.

2. Stewart, C. R., Chernoff, K. A., Wildman, H. F., & Lipner, S. R. (2020). Recommendations for medical student preparedness and equity for dermatology residency applications during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 83(3), e225–e226.

3. Cahn, B. A., Harper, H. E., Halverstam, C. P., & Lipoff, J. B. (2020). Current Status of Dermatologic Education in US Medical Schools. JAMA dermatology, 156(4), 468–470.

4. Patel, P. M., Tsui, C. L., Varma, A., & Levitt, J. (2020). Remote learning for medical student-level dermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 83(6), e469–e470.

5. Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71.

6. Lipner, S. R., Shukla, S., Stewart, C. R., & Behbahani, S. (2021). Reconceptualizing dermatology patient care and education during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. International journal of women's dermatology, 7(5), 856–857.

7. Ashrafzadeh, S., Imadojemu, S. E., Vleugels, R. A., & Buzney, E. A. (2021). Strategies for effective medical student education in dermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 84(1), e33–e34.

8. Su, M. Y., Lilly, E., Yu, J., & Das, S. (2020). Asynchronous teledermatology in medical education: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 83(3), e267–e268.

9. Belzer, A., Olamiju, B., Antaya, R. J., Odell, I. D., Bia, M., Perkins, S. H., & Cohen, J. M. (2021). A novel medical student initiative to enhance provision of teledermatology in a resident continuity clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic: a pilot study. International journal of dermatology, 60(1), 128–129.

10. Linggonegoro, D., Rrapi, R., Ashrafzadeh, S., McCormack, L., Bartenstein, D., Hazen, T. J., Kempf, A., Kim, E. J., Moore, K., Sanchez-Flores, X., Song, H., Huang, J. T., & Hussain, S. (2021). Continuing patient care to underserved communities and medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic through a teledermatology student-run clinic. Pediatric dermatology, 38(4), 977–979.

11. Muzumdar, S., Grant-Kels, J. M., & Feng, H. (2020). Medical student dermatology rotations in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 83(5), 1557–1558.

12. Alikhan, A., Sivamani, R. K., Mutizwa, M. M., & Aldabagh, B. (2009). Advice for medical students interested in dermatology: perspectives from fourth year students who matched. Dermatology online journal, 15(7), 4.

13. Fernandez, J. M., Behbahani, S., & Marsch, A. F. (2021). A guide for medical students and trainees to find virtual mentorship in the COVID era and beyond. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 84(5), e245–e248.

14. Creagh, S., Pigg, N., Gordillo, C., & Banks, J. (2021). Virtual medical student radiology clerkships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Distancing is not a barrier. Clinical imaging, 80, 420–423.

15. Pei, L., & Wu, H. (2019). Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical education online, 24(1), 1666538.

16. Mheidly, N., Fares, M. Y., & Fares, J. (2020). Coping With Stress and Burnout Associated With Telecommunication and Online Learning. Frontiers in public health, 8, 574969.

17. Janopaul-Naylor, J., Qian, D., Khan, M., Brown, S., Lin, J., Syed, Y., Schlafstein, A., Ali, N., Shelton, J., Bradley, J., & Patel, P. (2021). Virtual Away Rotations Increase Access to Radiation Oncology. Practical radiation oncology, 11(5), 325–327.

18. Tucker, A. B., Pakvasa, M., Shakir, A., Chang, D. W., Reid, R. R., & Silva, A. K. (2022). Plastic Surgery Away Rotations During the Coronavirus Disease Pandemic: A Virtual Experience. Annals of plastic surgery, 88(6), 594–598.